|

All about Corn > Corn and Mexico

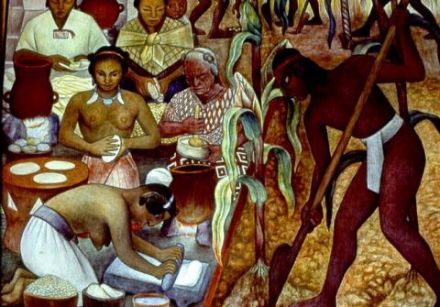

A look into the cooking of Mexico will lead you on a journey back to pre-Columbian times, some 700 years before the Christian era. The Meso-American civilization, or "corn" civilization, was already well-established. The staple food of all the Indian tribes, corn was the link between man and the gods, both a common bond and a source of quarrels among the tribes. Though the young ears could simply be boiled and the juicy kernels bitten off, Indian women learned other ways of using and cooking corn. They served it as a kind of porridge, "atole," for breakfast. When simmered with meat, it became "pozole," and the women transported it to the fields in gourds to feed the workers. Ground into flour, it was made into tortillas, the flat rounds that were either soft or crunchy, or into tamales, stuffed with beans or vegetables. Corn was also part of feasts: the flour, dissolved in water, was set aside to ferment in order to make a strong beverage flavoured with chilies or chocolate.

During the pre-Spanish period, while Montezuma's table was groaning under the weight of the many kinds of meat, game and fowl that abounded in the seemingly infinite land bordered by the two oceans, the daily diet of most people was frugal, consisting of three tortillas, chilies, highly seasoned dried beans or squash and a glass of atole: tortilla paste dissolved in milk, sweetened and flavoured with fruit or vanilla. But for special occasions, generally religious holidays, corn underwent a transformation. Such was the case during the month of Hueytozoztli, the great vigil. During April-May, tortillas were made in the shape of Chicomecatl, the goddess of subsistence, stuffed with dried beans and served with water flavoured with chia, the seed of a variety of sage.

Then in May-June came the month of the god Etzcualiztli. Corn was cooked with dried beans: a heavy food to signify abundance, whether of food or of rain. June-July saw the feast of the lords Huey Tecuhuitl and ceremonies dedicated to the goddess of the young ears of corn. Tamales were stuffed with meat or game, accompanied by water mixed with pinole (roasted corn flour); only the priests had the right to drink pulque, a fermented beverage made from agave, and an antecedent of tequila.

July-August paid homage to the sun god Huitzilopochhtli. The tamales became huge and might contain an entire turkey… or a fattened dog! They were decorated with flowers and feathers and adorned with pastry mixed with mushrooms to represent the warriors and other victims sacrificed to the sun god. The tamales were cut up and offered to the priests, accompanied by mountains of quails.

Then came the Spanish conquest and later revolution. The canteen women continued to form tortillas by hand. Then the Mexican flag was raised - ever since that day, Mexicans present their dishes in red and green, with tomato or red or green pepper sauces to represent the colours of their flag. On holidays, even the tortillas are coloured.

Manuel's grandmother still uses a three-footed mortar and a stone pestle to grind corn kernels, just as her Mayan ancestors did. She explains that when dried they will keep for a long time and can be eaten boiled in water; cooking swells them and they become tender like pasta.

-

Recipes

Recipes

-

Products

Products

-

Entertaining

Entertaining

-

Chefs

Chefs

-

Hints & Tips

Hints & Tips

-

Glossaries

Glossaries