|

All about tomato > A Short History of the Tomato

Origin: Tropical Americas, Peru in particular

Etymology: The word tomato is a corruption of the Inca word Tomalt; when the Incas extended their domination over the Andean plateaus in the 12th to 16th centuries they gave this name to the fruit; from Peru the tomato went to Europe where the etymological transformation occurred.

In Mexico we find the Nahualt word “jitomalt.”

Its Latin name Lycopersicum translates rather unappealingly as “wolf peach.” In the 18th century the adjective “esculentum” was added to the tomato’s botanical name because of the flavourful characteristics of this vegetable-fruit which until then had fared poorly in popular opinion.

Peru

Discovered in the 16th century by Spanish conquerors in South America who thought they had found the route to the Indies, the tomato was being grown by the Incas of the Andean region and at that time was no larger than the modern cherry tomato.

Spain

The tomato first appeared in Europe in the gardens of several monasteries around Seville that specialized in cultivating curiosities from the New World and other regions. The Moors who had invaded Spain were enchanted by this heart-shaped vegetable that seemed to represent love, and they carried it with them as they went on to conquer the whole Mediterranean basin. Seductive and bewitching, the tomato radically changed the cuisine of these sunny regions and even stormed Paris at the same time as the citoyens of the Revolution.

The Incas never suspected that their Mala Peruviana – apple of Peru – would become the subject of so many debates.

Italy

The tomato was long looked upon as an aphrodisiac. The first mention of it dates back to 1544 when the Italian herbalist Pierandrea Matthioli nicknamed it the “pomi’doro” or “golden apple” and classified it alongside the mandrake. It didn’t take long before the tomato was categorized among sexual stimulants, acquiring the name of “love apple.”

Great Britain

A few years later, John Gerard, a renowned English physicist and herbalist, learning that the tomato was beginning to be consumed in Italy and Spain, wrote in a memoir that it was toxic and ought not to be eaten in any form. He even stipulated that though it had pharmacological applications for treating gout and ulcers, there were other plants with similar recognized properties that could be used instead, since the tomato’s harmful effects made it not worth the risk. Because of his categorical refusal to classify the tomato as a food, it languished as an ornamental plant in English gardens and it was not until 1728 that gradually a few wedges began to be added into soup pots.

USA

In North America, the tomato had both enthusiasts and detractors, as well as a large number of unconvinced who stood somewhere in between. Seeing the tomato as something beautiful and tempting, the Puritans regarded the tomato as a sin to be grouped alongside dancing, drinking and card-playing. Scientists claimed that its relationship to the shocking mandrake and the mysterious belladonna, all members of the Solanaceae family, could have left residual effects that would gradually destroy a person. It had, after all, been called the Mala Insana by the Italian botanist Pierandrea Mattioli! As for witches and alchemists, the sulfurous smell given off by the tomato’s relatives and its bright red colour seemed to hint at some diabolical connection – and the tomato more often found its way into their smoking cauldrons than it did into the cook’s soup pot.

In 1800, inhabitants of South Carolina began exporting seeds and recipes into neighbouring states. In 1806 the American Gardener’s Calendar stated that the tomato enhanced the flavour of soups and sauces. Three years later, Thomas Jefferson came to the defense of this alluring fruit. He began cultivating it in his garden at Monticello and everyone who stopped by was invited to dinner where the dishes were enhanced by subtly-flavoured bits of red, to the great surprise of the guests.

As time passed, and as the tomato adopted new robes of scarlet, red, yellow or green, old superstitions persisted in most households. Although the Creoles of New Orleans had opened their doors to the tomato in 1812, eating a kilogram of tomatoes was an exploit that doctors from Massachusetts predicted would prove deadly on September 25, 1820. Robert Gibbon Johnson, a forty-year-old colonel and a respected figure from the town of Salem, was going to attempt to eat two pounds of tomatoes in front of 2000 people assembled before the court house on a fine fall day to prove that this lovely red vegetable-fruit was nature’s healthful gift to delight the eye and the taste buds. The public waited feverishly. No one had ever before dared to put such a belief into practice. Like an actor, walking onto the stage with his basket in hand, Johnson slowly and contentedly ate the tomatoes, one by one. Whether he displayed some disappointment as he reached out for the last tomato, as if he could have eaten more, history doesn’t say. But one fact is certain: he went away full and happy and died… forty years later!

However, the big tomato revolution in the United States took root with an article by Dr. John Bennet in 1834 in which he praised the tomato’s virtues to such an extent that the New York Times remarked on a spectacular increase in tomato cultivation. Tomatoes became all the rage. The media attention brought down the last barriers of opposition and editors began publishing recipes, gardening magazines and medical articles. Tomato pills even appeared on the market in 1837. Miracle cures were attested to. It was said that the tomato cured chronic coughs and kept away cholera. What was more certain was that Americans had unknowingly discovered a new source of vitamins.

However, tomato salads, sandwiches and uncooked sauces were still unknown. Until the 1930s, it was still claimed that eating a raw tomato was tantamount to suicide and it took at least three hours of cooking to dispel the old fears. Luckily for us, tomatoes are now part of our daily diet, and biting into a juicy and freshly cut tomato, bursting with the flavours of earth and sun, is one of the great pleasures of summer.

Many people wonder, and rightly so, whether the tomato is a fruit or a vegetable. Let’s settle the question once and for all: the tomato is a fruit. It required a Supreme Court decision in 1893 to reclassify the tomato as a vegetable for commercial reasons, but botanically speaking, the tomato remains a fruit…. even if enjoyed as a vegetable!

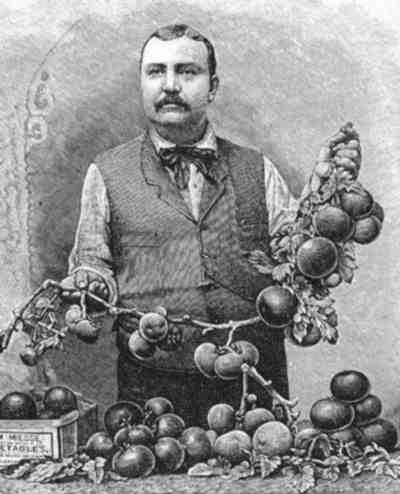

Illustration : Plant breeder Mr. Miesse with his "Maule's 1900"

tomato, as they appeared in Maule's Seed Catalog

-

Recipes

Recipes

-

Products

Products

-

Entertaining

Entertaining

-

Chefs

Chefs

-

Hints & Tips

Hints & Tips

-

Glossaries

Glossaries