|

Culinary tour

Marrakech is awakening. As every morning for the last 800 years, in the same chanting inflections, the muezzin’s call to prayer resonates from the heights of the 70-meter tall Koutoubia, the spiritual beacon of Marrakech. The sun rises and a colorful crowd begins to fill the winding streets of the medina. Carts filled with oranges and roasted grains, women who have come from Anti-Atlas to sell their baskets, story tellers, musicians, public letter-writers sitting behind black umbrellas, fortune tellers, apothecaries… these are all part of the dizzying spectacle that is just another day in Morocco.

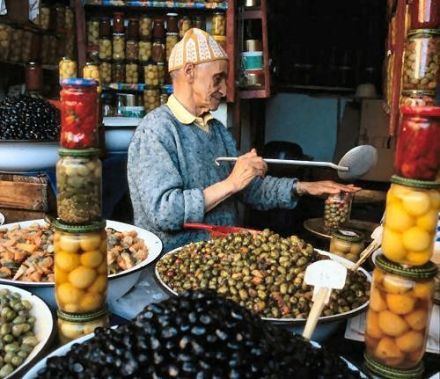

In the souks of Fez, the coppersmiths begin fashioning tea makers and pots. The aroma of the olive market fills the air. Pastries are stacked in tempting piles: doughnuts, “gazelle horns,” date cakes.

In Rabat, in the shadow of the Oudayas’ casbah, the fortress of the invincible Andalusian corsairs of the 17th century, the men gather in the Moorish café, discussing business over steaming glasses of mint tea, sometimes letting their gaze drift to the far off boats floating in the Oued Bou Regreg at the foot of the Salé ramparts.

In Agadir, the world’s leading sardine-fishing port, the sirens sound, multicolored trawlers pull into port, men with deeply-lined faces repair their nets, and throughout the day fishermen noisily unload crates of wriggling fish, sardines, whiting, sea bass, mullet and tuna, as well as shrimps, lobsters and langoustes.

Morocco is heir to a 2000 year old culinary tradition that has absorbed many sweet influences. From the Persians comes a tradition of combining meat with fruit, and from the Turks, a love of sweets and icing sugar. Take for example, pastilla, the jewel of Moroccan cuisine: a flaky pastry with a sweet and savory filling, spiced with cinnamon. There are some modern variations made with fish, seafood or offal, but pastilla is always a festive dish served at the beginning of a meal, which can include up to 50 layers of thin pastry that enclose a delicate mixture of onion, pigeon (or chicken), parsley, hardboiled egg and almonds. There are also briouats, beef turnovers, served hot and arranged in a ring around a dish of icing sugar and cinnamon.

In contrast to this culinary refinement stands couscous, which represents the cooking of the peasants: semolina cooked in hot broth or sauce. For the Berbers, it is flavored with sheep or goat’s milk. It’s the traditional Friday family lunch and varies by region; it may be served with lamb, chicken and olives, chicken and prunes, merguez sausage, etc. Made from durum wheat semolina, couscous is cooked by steaming. To eat it, one traditionally takes a handful of semolina and forms it into a ball with one hand. Couscous is cooked in a couscoussière which consists of a pot in which the chicken or lamb and vegetables are cooked, on top of which is placed a second lidded vessel filled with holes that allow the steam from the meat to penetrate and cook the couscous while imbuing it with delicious flavor. Once cooked, the couscous is arranged in a mound on a large platter and a well is hollowed out in the center to hold the meat and vegetables.

Moroccans like rich floral flavors like saffron, cumin and coriander. Every cook prepares his own spice blend for flavoring soups and stews. Kama is a mixture of black pepper, turmeric, ginger, cumin and nutmeg.

Lamb and mutton are staples of Moroccan cooking. The latter even has its own feast day, called Aïd el-Kebir or Aïd el-Adha, commemorating Abraham’s sacrifice. The mutton feast takes place on the first of Moharrem, the first day of the Hegira in the Muslim calendar. Chicken also features prominently in the cuisine, and sometimes goat as well, depending on the region.

Meat is cooked on skewers (mechoui) or in tagines, a long-simmered stew containing fruit (particularly dates, prunes and preserved salted lemons), cooked in a glazed terra cotta vessel with a tall pointed lid like a witch’s hat. It allows the steam to rise and then descend again, creating a perfect environment for slow cooking. In winter, particularly in the mountains, temperatures can drop quite low. The tagine is placed on the coals of the fireplace and a little more spice is added to provide even more of a warming effect.

Another typical utensil and a very popular dish is tanjia marrakchia. The name refers both to the squat earthenware cooking vessel and to the spiced lamb dish that is prepared in it. All the ingredients are thrown in and stirred up, and then the dish is simply tied up with paper and string and brought to the hammam where the “farnachi” covers it in hot ashes and leaves it to cook for at least four hours.

This is a dish made by men for men, a treat prepared by bachelors for a party or an outdoor gathering accompanied by music and card playing.

In Morocco, you’ll also find dishes prepared in casseroles, in which meat is seared in smen, a strongly-flavored butter. Then water, onions, spices and cinnamon are added and the dish is left to simmer.

Many Moroccans begin their day with a bowl of soup. Harira is the national soup. During the 30 days of Ramadan, every household prepares this flavorful dish that fills the streets with its aroma as soon as the sun goes down. The day’s fast (f’tour) is then broken with this rich concoction of meat, lentils and chickpeas. It is eaten with beghrirs, little waffles served with melted butter and honey, and shebbakias, little cakes fried in oil and dipped in honey. This “light” snack holds Moroccans over until the real dinner is served later in the evening.

Chermoula is a basic seasoning for fish in Moroccan recipes, whether fried, cooked with vegetables in a tagine, or stuffed and baked. It consists of coriander, garlic, sweet and hot peppers, cumin and coarse salt mixed with lemon juice and olive oil.

A traditional meal wouldn’t be complete without fruit, and especially a wide selection of pastries.

Mahancha - thin pastry filled with almonds

Righaif – pancake with honey and sesame seeds

Honey cakes

“Gazelle horns”

Feqqas with almonds and raisins

Ghoriba with almonds and sesame

Shabbakia – small cakes fried in oil and coated with honey

Mint tea is offered as a sign of hospitality. It is served very hot and very sweet at all hours of the day, whether you’re at the carpet merchants, in a Berber tent or in the lobby of a big hotel. Presented in a small narrow glass, it is poured from a great height in order to remove any bitterness. You may also come across chiba, an absinthe tea.

Then as evening falls the inexpensive restaurants open up. As the stars come out and the oil lamps are lit, the aroma of roast meats, couscous, harira and doughnuts fills the air. In the medina, the spectacle continues in the market place (souk), a labyrinth of shadow and light branching out endlessly under reed trellises, a blur of color, sound and scents that draw you into the rhythm of the crowd, inviting you to delve more deeply into this exotic culture.

Go out onto the terrace and breath in the mellow night air. The dishes will be laid out on the low table – time to relax and enjoy life.

- Garlic

- Cinnamon

- Cayenne pepper

- Curcuma

- Chermoula

- Salt-Preserved Lemons

- Cumin

- Coriander seeds

- Orange blossom

- Ginger

- Clove

- Harissa

- Kama

- Honey

- Ras-el-hanout

- Safran

- Tabel

Photo above National Board of Morocco

-

Recipes

Recipes

-

Products

Products

-

Entertaining

Entertaining

-

Chefs

Chefs

-

Hints & Tips

Hints & Tips

-

Glossaries

Glossaries